The Rockhill Iron & Coal Company

Historical Overview

"Juniata Iron"

The phrase conjures images of flat-topped stone pyramids and 'ancient' stone ruins dotting the rural landscape of 21st-Century Central Pennsylvania, the remnants of a long-gone era. During the late-Eighteenth and early-Nineteenth centuries the Juniata region (encompassing the counties of Bedford, Blair, Huntingdon, and Mifflin) was an important part of Pennsylvania's iron industry, especially the foundries and rolling mills of Pittsburgh. By the mid-19 Century, according to historian Kenneth Warren, the water-powered charcoal iron furnaces and forges of the Juniata region produced 40% of the pig and wrought iron consumed by the foundries and rolling mills of Pittsburgh.

During the 1870s coke began to replace charcoal as the principal fuel for producing pig and wrought iron. Coke, which is a contraction of "coal cake," is a nearly pure-carbon fuel made by heating bituminous coal in an oxygen-poor environment. Its stronger load-bearing capacity enabled the construction of blast furnaces much larger than traditional charcoal blast furnaces. Furthermore, it could be made year-round and transported in bulk over large distances. All of these advantages over charcoal led to the rapid expansion of iron and steel making in Pittsburgh and other industrial cities in western Pennsylvania.

The discovery that bituminous coal from the isolated Broad Top coalfield in northern Bedford and southern Huntingdon counties produced high-quality coke gave rise to an iron-making district based on coke and still-plentiful iron ore n the Juniata region.

An Iron-making District Built on Coal & Coke

Between 1868 and 1884 four companies built coke-fired blast furnaces on the fringes of the Broad Top coalfield. The Rockhill Iron & Coal Company was one of them, going into blast at Rockhill in 1876. The others, located on the Raystown Branch Juniata River in Bedford County, were as follows:

- Kemble Coal & Iron, Riddlesburg, 1868

- R. H. Powell Co., Saxton, 1882

- Everett Iron, Everett, 1884

The Rockhill Iron & Coal Company ...

... grew out of the old charcoal iron industry near the Borough of Orbisonia and a new firm that hoped to develop its coal property in the Broad Top coalfield. Iron ore deposits under Blacklog Mountain, which extends from the Juniata River opposite Mifflintown southwest to Blacklog Creek near Orbisonia supported three sporadically operated charcoal iron furnaces near the latter place between 1785 and the 1840s. The most consistent of them was Rockhill Furnace, which went back into blast briefly during the Civil War. In 1867 Percival P. Dewees, a Philadelphia-based capitalist, bought and reconditioned the works. But for some reason (probably depletion of the old mines in the immediate vicinity) his enterprise suffered from lack of ore. Dewees discovered new ore deposits north of Three Springs, about six miles west of Orbisonia, but the difficult wagon-haul over unimproved roads was a costly problem.

Iron and Coal Interests Combine

Meanwhile a group of Dewees' fellow Philadelphians had gotten control of thousands of acres on the east side of the Broad Top coalfield, but they had yet to develop it. Realizing the potential for a successful modern blast furnace based on coking coal from the East Broad Top coalfield and Dewees' new sources of iron ore, the two groups joined forces to form the RI&C.

The RI&C partners revived an old railroad charter for the East Broad Top Railroad, which they built to connect their coal mines at Robertsdale to a new blast furnace complex across Blacklog Creek from the old charcoal furnace. The railroad would also ship their pig iron and excess coal to distant markets via a connection with the Pennsylvania Railroad at Mt. Union.

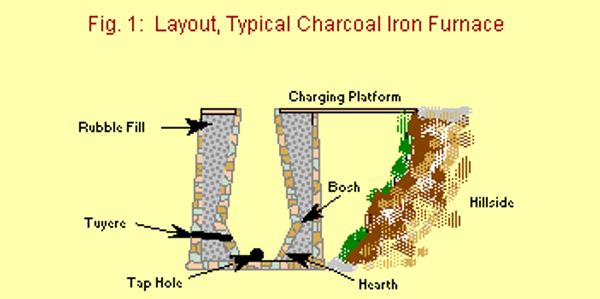

You can download "An 1870s Iron Making Primer" below to learn about how pig iron was manufactured by RI&C and its predecessors.

1870s Iron Making Primer (pdf)

Download

Between 1876 and 1893 RI&C was a completely self-sufficient merchant pig iron company, making pig iron for sale on the open market. The company built a 3-ft. gauge tram line from a junction with the EBT yard near the Rockhill station (renamed Orbisonia station in 1903) extending into Blacklog Narrows to serve the blast furnace, iron mines and limestone quarry. SEE Map at left.

In the mid-1880s the Shade Gap RR, chartered by several of the EBT's directors, built a narrow gauge line from the end of the RI&C tram at Blacklog station to Shade Gap. Between 1885 and 1890 the iron and coal company leased five iron mines in Shade Valley. The SGRR built the Shade Valley Branch north from Shade Gap station as far as the RI&C mine at Nancy, while the RI&C added an extension of its own from there to Richvale. Members of RI&C also built the Booher Branch Railway to tap an ore deposit southwest of Rockhill. The EBT operated all of these lines under lease agreements. The map shows the RI&C's tracks in red.

Company Towns

RI&C built three company towns to house its workers. Rockhill, which the company originally called "Cromwell," housed the managers and workers of the iron and coke complex as well as employees of the EBT. This site became the operating hub of the EBT. The new company town, which was situated on the opposite side of the EBT's Rockhill yard from the blast furnace and coke ovens, usurped the name of the "old" Rockhill Village that had grown up around the charcoal iron furnaces in Blacklog Narrows. In 1900 the census differentiated between the "old" and "new" Rockhills. But by 1910 "new" Rockhill was a newly chartered borough in its own right, and "old" Rockhill had essentially disappeared -- its remnants reduced to being the outskirts of Orbisonia.

An illustrated essay on the blast furnaces of RI&C a how they worked.

The Rockhill Furnaces (pdf)

DownloadRI&C ran its blast furnace continuously and successfully until the Panic of 1893 led to a depression in the iron and steel market. Contemporary newspaper accounts suggest that the company intended to keep the furnace going with reduced wages. But a strike by native-born workers and violence directed by the strikers against Rockhill's small community of Eastern European immigrants, who wanted to continue to work, decided the issue. The Rockhill Furnace sat idle until 1902.

In 1902 a group of RI&C directors formed the Rockhill Furnace Company to lease and operate the Rockhill furnace. But a lot had changed in the nine years the plant lay idle. First, the plant was obsolete even by the standards of its counterparts in Bedford County. Moreover, the Shade Valley ore leases had expired and the land owners were not favorably disposed to new leases. RFC was forced to turn to outside sources for its iron ore, which increased both the base cost and transportation cost of the essential raw material. Despite these problems, however, the company kept the furnace in blast at a higher rate of output than during the 1880s.

Another depression following the Panic of 1907 idled the Rockhill Furnace again, and it never went back into blast. Popular legend has it that the Rockhill Furnace died because it couldn't compete with the large integrated iron and steel firms that emerged in the early 20th Century. But like all of the legends surrounding RI&C and the EBT, this one does not stand up under scrutiny.

All three of the Rockhill Furnace's counterparts on the Raystown Branch survived under small, independent merchant pig iron firms into the early 1920s; the Riddlesburg furnace lasted into the early 1940s! In fact, none of the Raystown Branch blast furnaces were idle for more than two years following 1893. Had RI&C wanted -- or been able -- to compete with its neighbors between 1895 and 1902 it could have put its furances back in blast. But it did not do so, nor did RI&C chose to re-enter the pig iron market after the brief depression following the Panic of 1907. While the coal & iron companies along the Raystown Branch modernized their blast furnace plants prior to World War I, RI&C scrapped its furnace complex while modernizing its coal production facilities. The fact that prosperity came to firms on both sides of the Broad Top coalfield suggests that that decision by the directors of the Rockhill Iron & Coal Company to abandon pig iron production was made, not forced.

Sources:

Annual Reports of the East Broad Top Railroad to the State Auditor General. Records of the Bureau of Statistics in Records of the Department of Internal Affairs, Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg, PA.

Jon D. Baughman, Men of Iron: A History of the Iron Industry of South-Central Pennsylvania, 1785 - 1950 (Broad Top Bulletin, 1998).

Contemporay Newspapers of Huntingdon County, PA, especially the Huntingdon Globe and the Huntingdon Journal. Microfilm collecion of Beeghly Library, Juniata College, Huntingdon, PA.

Directories of the American Iron and Steel Association. Reference Collection, Science and Technology Department, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

Lee Rainey and Frank Kyper, East Broad Top (Golden West Books, 1982).

Lee Rainey, "The EBT in the Iron Age, Pt. 1 - 4," in Model Railroad Craftsman, March - June 1990.

Kenneth Warren, The American Steel Industry, 1850-1970: A Geographical Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), 29-31

Company Towns

Robertsdale

Robertsdale

Robertsdale

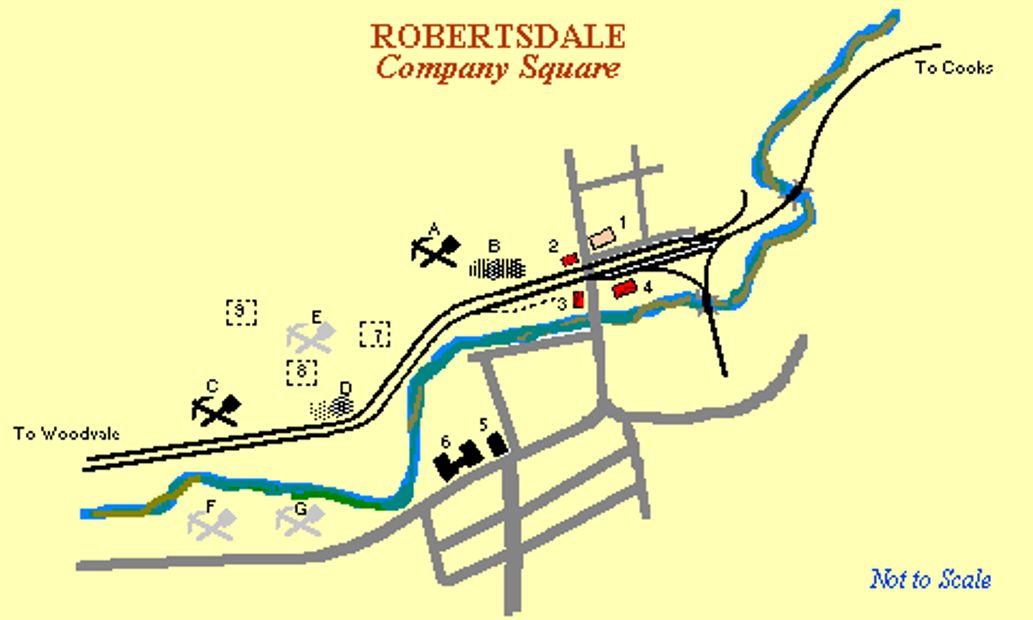

Built in 1873 to house miners & their families, this became the operating hub of the East Broad Top RR in the Broad Top Coal Field.

Woodvale

Robertsdale

Robertsdale

Built ca. 1890 to house miners and their families when the RI&C expanded its operations southward from Robertsdale.

KEY

1 - RC&I Company Store (1874)

2 - EBTRR Depot (ca. 1917)

3 - Old Post Office (1915)

4 - RC&I Offices (ca. 1917)

5 - Reality Theater (1948)

6 - School (1934)

7 - Mule Stables site

8 - Rockhill No. 5 Boiler House ruins

9 - Fan House

Mine and tipple locations denoted by letters and covered in the text.

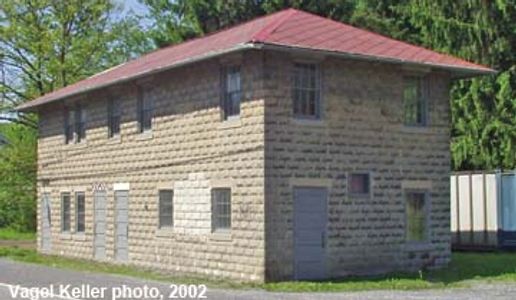

The "Company Square" ...

... was once the planned center of tourist operations should the EBT ever be restored along its entire length. It consisted of the EBT station, center background, the Post Office, left, the coal company office building, corner visible at right, and the coal company store. All but the store are still extant. Map ref. 1 - 4.

The EBT replaced its original Robertsdale station, a small wooden structure, with this rusticated block structure ca. 1917. The Kovalchick family, who currently own the EBT and coal company properties, sold it in the 1980s. The Friends of the EBT, a 501.c.3 nonprofit "dedicated to preserving and restoring the EBT," leased it from the new owner and restored its exterior and interior. FEBT now owns it. The station houses part of the FEBT's collection of RR artifacts.

On the opposite side of the tracks from the site of the Company Store stands the two-story rusticated block RI&C office building. Today, the Robertsdale Post Office occupies the ground floor. During the company's active years, however, the post office occupied the ground floor of the two-story rusticated block structure that stands across the street. Both the office building and the "old post office" date to approximately the same period as the EBT station.

The EBT installed a "wye" for turning locomotives at Robertsdale, and the tracks are still in place. The detail photo shows the wye rails curving around the northwest corner of the office building.

The post office was in the company store until the RI&C built the structure at right at about the same date as the office building. The post office occupied the western half of the ground floor, at right in this view, while a barber shop once occupied the east end. The second floor was the post master's residence. FEBT now owns it and recently finished restoring it to house its collection of artifacts and research materials.

At the center of town, the company built a large random stone structure in 1874 to house the Company Store. Long abandoned and steadily deteriorating, it was demolished in March, 1997 after being declared a public health hazard by the local government.

The Robertsdale Mines

KEY

A - Rockhill No. 1

B - Rockhill No. 1 Tipple site

C - Rockhill No. 5

D - Rockhill No. 5 Tipple site

E - Rockhill No. 3 site

F - Rockhill No. 4 site

G - Rockhill No. 2 site

In 1890 mine No. 5 (Map ref. C) replaced No. 3. Archaeological evidence and contemporary maps indicate that the company superimposed the tipple, shown at right, for mine No. 5 on the old tipple for mine No. 3 (Map ref. D). Rockhill No's 1 - 4 were drifts (following the coal seams from their outcrops on the surface) opened in the early 1870s.

In 1890 mine No. 5 (Map ref. C) replaced No. 3. Archaeological evidence and contemporary maps indicate that the company superimposed the tipple, shown at right, for mine No. 5 on the old tipple for mine No. 3 (Map ref. D). Rockhill No's 1 - 4 were drifts (following the coal seams from their outcrops on the surface) opened in the early 1870s.

RI&C operated a coal preparation plant at Robertsdale during the years that the Rockhill furnaces were in blast. The plant included a crusher and a sluice-type washer that processed clean, fine coal for the coke ovens at Rockhill. Archaeological evidence suggests that the plant was attached to the Rockhill No. 3, and later No. 5, tipple until the turn of the 19th Century. Mine No. 5 was a slope mine, which reached the seam below the surface from an inclined tunnel. The opening, at left, has been partially covered by the collapse of the retaining wall, at left, since this photo was taken in 1991.

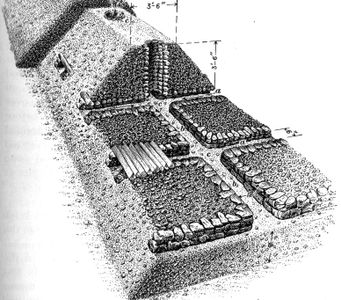

From 1876 until the mid-1880s the company also made coke in "coke pits" at Robertsdale. The would have been similar to those shown at right. This technology preceded the familiar "beehive" ovens and was essentially the same process as that used in making charcoal. Although their life-span is unknown at the present time, it is possible that RI&C used the coke pits until the early 1880s when the company built beehive ovens at Rockhill to supplement -- and eventually replace -- the Belgian-style coke ovens it had originally built.

The sites of the coal preparation plant and the coke pits are not known precisely, but archaeological evidence suggests that they were in the general vicinity of mine No. 5. Traces of coke have been found in shallow depressions beside the EBT's tracks near the opening of mine No. 5. Other archaeological evidence suggests that the coal preparation plant was linked to the No. 3 tipple just south of the ruins of the later No. 5 tipple. It is clear that the area around (and under) the surface structures at the No. 5 tipple hides the secrets of the early decades of the RI&C's coal production at Robertsdale.

Robertsdale grew rapidly, from a few dwellings, a mule stable, and blacksmith shop in 1874, to 479 people and 27 houses in 1876. By 1880, there were 694 people in Robertsdale, with 119 households in 57 houses. By 1910, the number of families grew to 262, with an average family size of 5. Many mining families took in borders. The great majority of houses in the town were two-story duplexes, but white collar workers and some railroad employees occupied a few large, single-family dwellings. In 1948 RI&C began selling houses to the miners, who immediately began to improve them (the first improvements invariably being indoor plumbing). Over the years, the exteriors of many houses were altered based on the prosperity of the owners, and some duplexes were converted to single family dwellings. Nevertheless, the street plans of both towns -- indeed, even their demographics -- have changed little.

The town of Robertsdale and the remains of railroad and mine facilities nearby (such as the ventilation fan house pictured here) are a virtual time capsule of work and life in the Appalachian coal regions.

Sources:

Second Geological Survey of Pennsylvania: 1875. Special Report on the Coke Manufacture of the Youghiogheny River Valley (1876). Collection of Drake Well Museum Library.

Interstate Commerce Commission Valuation Map of EBT (1917). Collection of FEBT.

Lee Rainey and Frank Kyper, East Broad Top (Golden West Books, 1984).

Lola M. Bennett, The Company Towns of Rockhill Iron and Coal Company: Robertsdale and Woodvale, Pennsylvania (U. S. Department of the Interior, 1990).

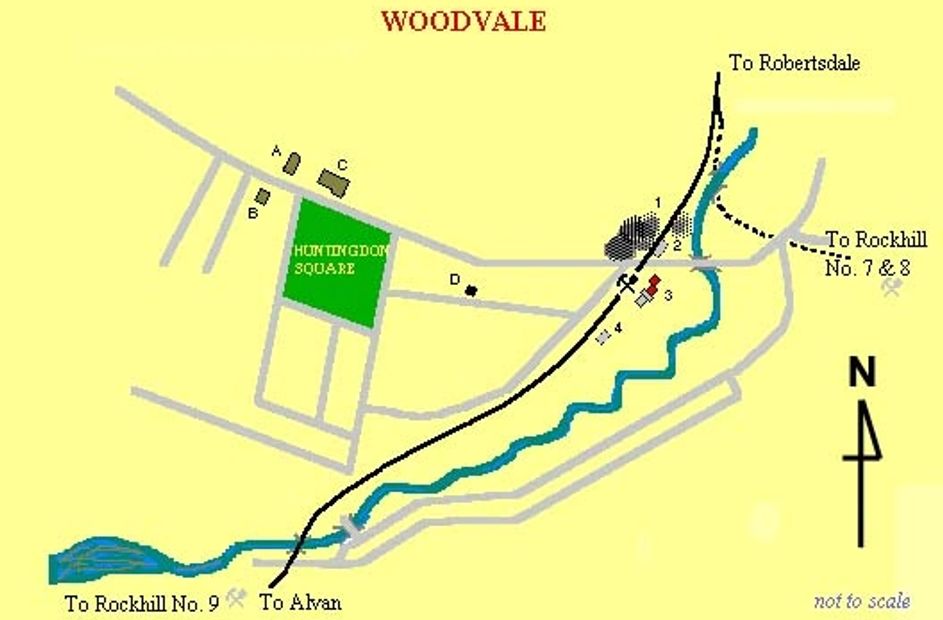

KEY

1 - Truck Dumps (ca.1941)

2 - Site of Mine Repair Shop

3 - Rockhill No. 6 Power House

4 - Site of Mule Barn

A - St. Michael's Church

B - St. Michael's Social Hall

C - Methodist Church

D - Woodvale Post Office

The Rockhill Iron & Coal Company (RI&C) established Woodvale in 1891, when it opened mine No. 6, its only vertical shaft mine. The mine was served by the 3-foot gauge East Broad Top Railroad, which extended its tracks to the mine head from the older coal company town of Robertsdale. During World War I, RI&C opened three drift (or slope) mines nearby. Rockhill No's 7 and 8 shared a common tipple at the end of a spur east of Woodvale, while Rockhill No. 9 was opened about a mile south of Woodvale at Alvan, which was simply a place name on the railroad. No. 6 was closed in 1925, but No's 7 and 8 operated until 1937

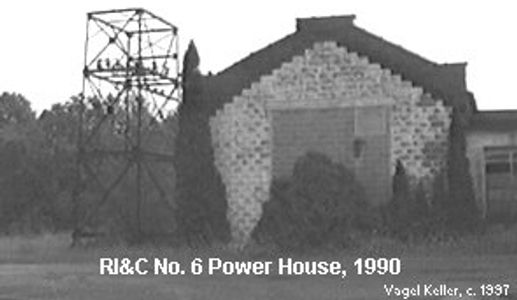

The overview of the No. 6 tipple and mine and support buildings, looking northeast, was probably taken during or shortly after World War I. The north end of the power house, below, still greets drivers-by as they enter the village. The power house supplied electricity to the new mines south of Woodvale, as well as for both company towns and the mines to the north.

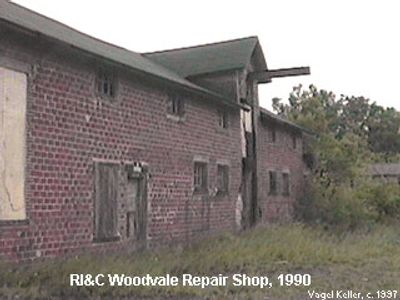

The coal company built a red block repair shop (pictured below, left) across the road from the No. 6 mine head. Mine cars and other equipment were repaired in the small machine shop, which was a miniature example of the extensive belt-driven shop run by the EBT in Rockhill. This building stood abandoned for years, but finally succumbed to arson in 1993. It is pictured, below, as it appeared in 1990.

Mules provided the motive power in the underground galleries of Rockhill No. 6. They were stabled in a large wooden barn to the south of the mine head. This building (below) survived into the 1990s, used as a storage building by the furniture factory in the old power house. It, too, was lost to arson at the same time as the repair shop was burned.

Faced with acute manpower shortages in the rapidly expanding coal industry around the Turn of the Century, coal companies imported thousands of Eastern European immigrants and their families to work the new mines. Among the immigrants brought to Woodvale by the RI&C was a contingent of Carpatho-Russians. This community still thrives in its isolated mountaintop village.

Their distinctive onion domed Russian Orthodox Church, St. Michael's, is a prominent landmark. It and the nearby social hall were built in 1935 after fire destroyed the original 1917 church. Next door to St. Michael's, the Woodvale Methodist Church gives testimony to the ethnic diversity of the coal company towns.

Together with Robertsdale and the surrounding mined-out landscape, Woodvale is part of a truly priceless piece of America's industrial history. But Woodvale also bears stark witness to the fragility of historical structures. While politicians and preservationists talk, arson and apathy stalk the shrinking remnants of an increasingly tenuous link to the past.

Sources:

Lee Rainey and Frank Kyper, East Broad Top (Golden West Books, 1984).

Lola M. Bennett, The Company Towns of Rockhill Iron and Coal Company: Robertsdale and Woodvale, Pennsylvania (U. S. Department of the Interior, 1990).

Copyright © 2018 Vagel Keller - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder